Once your mare is pregnant, consider her nutritional requirements in three stages. The first stage is the first two-thirds of her pregnancy. During this time, the fetal size does not increase significantly and your mare should still be on a maintenance diet. Her body condition should stay constant, again without losing or becoming obese. A mare that is losing weight will have a hard time re-breeding, and an obese mare will have more trouble foaling due to weak muscles and condition. If necessary, this stage of pregnancy is the best time to adjust body condition because they can increase energy stores while nutrient demands are relatively low.

The second stage of your mare’s pregnancy is the last three months. In this time, the fetus increases about one pound per day, accounting for two-thirds of fecal growth. Energy, protein, calcium, and phosphorous requirements increase. When your mare is on a maintenance diet, good hays and grasses or legumes will usually be enough. Once into her last three months, it is a good idea to consider supplementing with concentrated feed sources.

The third stage of pregnancy is lactation. This stage requires by far the most nutrients and is a time of great physiological stress. The only other time that any horse’s nutritional requirements would be as high as during lactation is if they are in very intensive training. During this time your mare has to recover from the stress of parturition, produce milk, and often re-breed. All of her nutritional requirements will increase. During lactation, a healthy mare will produce 3% of her body weight in milk per day for the first three months, then 2% of her body weight in milk per day towards the end of lactation. If her nutritional needs are not met during lactation, her body condition will be affected the most. In extreme nutrient deficiency, milk production can decrease as well. As your mare’s milk production decreases, her feed intake should be adjusted as needed. At weaning, feed intake should be gradually decreased, allowing the mare to “dry up” faster and will prevent obesity. You should allow 7-10 days for mares to adjust to intake changes.

It is important to consult your veterinarian before any nutritional changes in your mare’s diet, and your veterinarian should be actively involved in your mare’s pregnancy. You can also contact your local Cooperative Extension office with any questions.

Gibbs, Pete G., and Karen E. Davison. “Nutritional Management of Pregnant and Lactating Mares.” Texas A&M University Department of Animal Science Equine Sciences Program. Web. 15 Feb. 2012. http://animalscience.tamu.edu/images/pdf/nutrition/nutriton-nutr-mgmt-pregnant-mares.pdf

“Nutrition of the Broodmare.” University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service. Web. 15 Feb. 2012. http://www.uky.edu/Ag/AnimalSciences/pubs/asc112.pdf.

Now that long awaited foals are on the ground and learning to run, buck, and play, it is time to consider measures that you as an owner can take to help them have a long happy life. One of these preventative health measures is vaccination against diseases that can have devastating effects on the horse including Tetanus, Eastern and Western Equine Encephalitis Viruses (aka Sleeping Sickness), Equine Herpes Virus (aka Rhinopneumonitis), Equine Influenza, West Nile Virus, and Rabies.

These diseases are all potential pathogens that your young foal may encounter at some point in their life. Although in your own personal horse community diseases like Sleeping Sickness may not seem like much of a threat, yet there are still cases that occur annually in which the horses that are infected become gravely ill, and may have lasting effects from the disease if they are lucky enough to survive, not to mention the monetary costs of supportive care to be treated while ill.

The protective antibodies produced as a result of vaccination are not only helpful in preventing disease, but they can also be the difference in living or dying after expose to a particular pathogen. A good example of this is West Nile Virus, which was considered to be very deadly for horses in the years following it’s arrive to the United States back in the 1999. The mortality rate (e.g. risk of dying from having disease) is considered to be about 33% for horses that contract West Nile Virus infections, but what is more important is that over 90% of non-vaccinated horses when infected developed grave clinical signs such as inability to stand and/or complete loss of ability to eat/drink that resulted in their death or humane euthanasia. By simply vaccinating your foals you give them a fighting chance against a disease that has proven in recent years it is still very much a problem. From personal experience of cases I saw in Louisiana in 2012, the two horses that survived out of the three we treated for confirmed West Nile infections had been vaccinated, while the third had not. Despite full supportive care, this unvaccinated filly quickly became severely uncoordinated, lost the ability to stand and then began having seizure like episodes before the owner elected to euthanize and stop her suffering. In these aggressive diseases, preventative care such as vaccination is often our best treatment.

That being said the American Association of Equine Practitioners in an effort to promote the health of the horse has put together a list of core vaccines that all horses should have regardless of where they reside in North America. This includes Tetanus, Eastern/Western Encephalitis, West Nile, and Rabies. Additionally vaccination for Equine Herpes Virus (e.g. EHV- 1 and 4) and Equine Influenza is also recommended for horses that will be showing, racing, or are house in densely horse populated areas such as boarding and breeding facilities. Because these are common pathogens that are easily spread between horses it is also a good idea to give foals an early advantage by vaccinating them against these diseases.

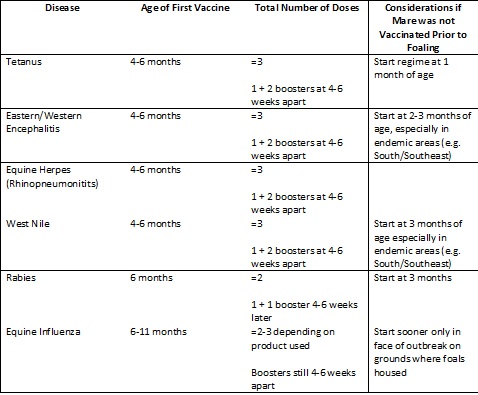

To help get the most protection out of vaccinating your foal it is best to vaccinate at specific times in the first year of the foals life. Below is a table that outlines the current recommendations for foal vaccinations:

Since there are difference types of vaccination products for diseases like West Nile and Equine Influenza consulting with your veterinarian will be the most effective way to create a vaccination program that will best benefit your foal. Also every situation is different and your veterinarian can help determine other pathogens your foal may at higher risk for based on geographical location and how the horses on your property intermingle. Examples of some other diseases to ask you veterinarian about vaccination for would be Strangles and Botulism as these can be huge problems for foals in certain circumstances.

Colostrum Bank

By Patrick M. McCue, DVM, PhD,

Diplomate American College of Theriogenologists

An owner or farm manager generally does not know in advance which foal will need supplemental colostrum. An on-site supply of frozen colostrum can be critical for the health of a valuable neonate.

The best colostrum donors are mares that have had one or more foals and are 4-15 years of age. Vaccination 4 to 6 weeks prior to foaling will increase antibody content of colostrum and consequently increase the quality of colostrum to be collected for storage. Colostrum volume and quality are not as good from young maiden mares or older mares. Mares that have dripped milk for several hours prior to foaling may not have a large volume of good quality colostrum remaining in their udder and may not make suitable donors for a colostrum bank. Colostrum should not be saved from a mare with a history of having a foal affected by neonatal isoerythrolysis (NI or Jaundice Foal Syndrome) or that died from unknown causes within the first few days after birth.

Good quality colostrum is thick, yellow in color and sticky in texture. Poor quality colostrum is often watery, white in color and non-viscous in texture. Colostrum quality (i.e. antibody content) can be estimated using a Brix or sugar refractometer. Good quality colostrum will have a refractive index of ³ 23 % when using a sugar refractometer. Brix refractometers are easy to use, require a minimum of colostrum (i.e. one drop) and results are highly correlated with IgG concentrations as determined by laboratory testing.

Ideally, colostrum to be banked should also be tested for the presence of anti-RBC antibodies, to prevent the possibility of inducing neonatal isoerythrolysis in a foal receiving stored colostrum. Testing for NI antibodies can be performed at the University of Kentucky and the University of California, Davis.

The technique for harvesting colostrum is relatively simple. The udder of the mare should be washed with warm water and soap to remove debris and bacteria. It is recommend that colostrum be collected from one side of the mammary gland from a donor mare in the first hour after foaling before her foal has nursed. A total of 8 to 16 oz may be safely harvested from the mare without adversely affecting the ability of the newborn foal to acquire sufficient colostrum for adequate passive transfer of antibodies.

Stripping or milking colostrum by hand directly into a clean glass or plastic measuring cup 16 to 32 oz in capacity will make it easy to evaluate the volume that has been collected. Alternatively, colostrum can be harvested using an inverted 60 ml syringe as a simple milking device. To make the unit, cut the tip off of a 60 ml plastic syringe. Reverse the syringe plunger (i.e. insert the plunger into the end the tip was removed from) and place the flared end of the syringe over the mare’s teat snug against the udder. A gently pull on the plunger will create suction and draw colostrum down into the syringe. The colostrum in the syringe is then transferred into a larger measuring cup and the process repeated until the desired volume is obtained.

Harvested colostrum should be passed through a gauze filter or new cheesecloth into a storage container. Colostrum should be stored in 8 to 16 oz plastic bottles labeled with the donor mare’s name, collection date and colostrum quality. Glass bottles or plastic freezer bags are not recommended for storage of frozen colostrum. Frozen equine colostrum can be safely stored for 1-2 years in a standard -20o C freezer. Colostrum should be harvested each breeding season to replenish the colostrum bank with a fresh supply. Colostrum that is > 1 year old can be used to supplement at-risk foals on the farm.

Frozen colostrum should be thawed in a water bath at room temperature. Thawing in hot water or in a microwave will destroy the antibodies and render the colostrum useless.

Colostrum is considered to be ‘liquid gold’ by horse breeders and veterinarians alike. Making deposits in the bank early and often during a breeding season will provide dividends for years to come.